On our website today, economist David Beckworth explains how the supply shock caused by the coronavirus can lead to a demand shock if the Federal Reserve does not cut rates.

A supply shock decreases demand for capital, bringing down the equilibrium interest rate. The expansionary or contractionary effect of monetary policy is determined by the difference between the federal-funds rate (FFR) and the equilibrium, or “neutral,” cost of money in the economy. If the FFR is below the equilibrium rate, monetary policy is expansionary, and vice versa.

As the equilibrium rate declines, the Fed “passively tightens” if it did not reduce interest rates accordingly.

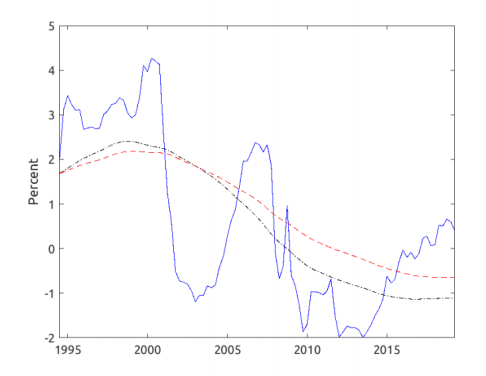

This kind of dynamic has been in the background of monetary policy for the past few decades, as the equilibrium rate has consistently fallen. Despite interest rates being at zero during the post-crisis expansion, monetary policy was much tighter during that period than during the early 2000s. According to one estimate, the Fed has been effectively tight since 2015. In the chart below (via Fed economist Michael T. Kiley), the blue line represents the effective real interest rate and the black-dashed line represents the real equilibrium interest rate.

This helps explain why, despite a decade of unprecedentedly low interest rates, inflation has remained below the Fed’s 2-percent target.