In another departure from the style of his predecessor, President Biden has resisted weighing in during the riveting murder trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

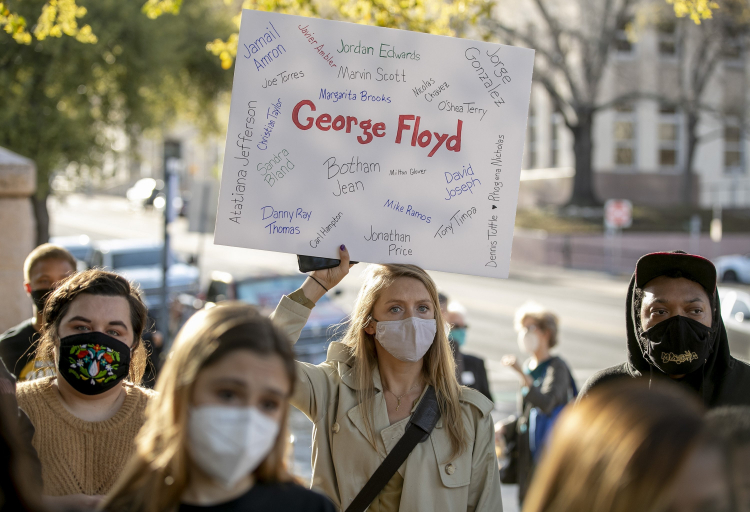

But the death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man whom Chauvin pinned to the ground for nine minutes with his knee on Floyd’s neck, had a profound impact on the 2020 presidential election. It sparked protests across the country, some of them violent, galvanized African American voters, and narrowed Biden’s choices for vice president, leading to the historic selection of Kamala Harris.

And when the trial in Minnesota comes to an end, the administration — and the country — will be left with a bigger challenge: finding a way to translate broad public support for police reform into sound policy so that tragic incidents like this one do not keep happening. For his part, the president vowed last summer, as clashes erupted between police and protesters, to establish a police oversight commission in his first 100 days.

“We need each and every police department in the country to undertake a comprehensive review of their hiring, their training and their de-escalation practices,” Biden said during remarks in Philadelphia last June. “And the federal government should give them the tools and resources they need to implement reforms.”

Biden still has several weeks to fulfill that pledge although he hasn’t provided any indication that he has begun the process. In his first two-plus months in office, the president obviously has been consumed with other pressing matters, including a humanitarian crisis at the border and the COVID vaccination rollout.

Pressed this week on whether Biden is on track to fulfill the police commission pledge, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki pointed to the president’s support for a police reform bill that passed the House in early March on a mainly party-line vote. That measure is stuck in the Senate with no sign of movement without a change to the upper chamber’s filibuster rules.

“This bill is an opportunity to put in place a number of the actions that he, that many in the advocacy community, feel are imperative at this point in our nation’s history,” Psaki said.

Dubbed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, the legislation would ban chokeholds and roll back so-called qualified immunity for law enforcement, a big change to legal doctrine that would make it easier to pursue claims of police misconduct in court. The wide-ranging measure would also ban no-knock warrants in certain cases, require data collection on police encounters, prohibit racial and religious profiling and provide more funding for community-based policing programs.

“Never again should an unarmed individual be murdered or brutalized by someone who is supposed to serve and protect them,” Rep. Karen Bass, a California Democrat, said in a statement when the bill passed the House on March 3. “Never again should the world be subject to witnessing what we saw happen to George Floyd.”

But a similar House bill passed last year only to die in the Senate, where Republicans have long opposed lifting qualified immunity protections for police in any significant way.

“We have work to do in the Senate,” Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, told RealClearPolitics. “The Senate is notoriously slow – we are working very hard to make sure that [senators] know that the provisions of the bill are very popular.”

The Democrats’ messaging strategy, Muriel said, should cite several polls showing widespread support for laws making it easier to hold police accountable for misconduct. A Pew Research Center survey in July found that 66% of respondents believe citizens should have the power to sue police officers for using excessive force. But the issue is far more complicated when questions about cutting funding to law enforcement are added to the mix. The same poll found that just 25% of Americans say spending on policing in their area should be decreased.

While liberals talk about reforming the police and “defunding” their departments in the same breath, that widespread opposition to defunding initiatives has made it a radioactive issue for many Democrats, especially in more moderate states and localities.

Rep. Abigail Spanberger, a centrist Democrat from a Virginia battleground district, angrily told House progressives after the November election that their “defund the police” movement nearly cost her her seat and was likely responsible for other Democrats losing theirs in swing districts across the country. While Biden won the presidency by more than 7 million votes, Democrats suffered a loss of 13 House seats, leaving them with a very slim majority.

And cities such as Minneapolis and Los Angeles that decreased police funding in the wake of last year’s racial unrest have experienced huge spikes in violent crime and have since backtracked after residents’ complaints that more police officers were needed.

During his campaign, Biden distanced himself from the defunding movement, calling instead for more money for training and citing the need for different tactics, including non-police responses for mental health emergencies. During a meeting in Georgia ahead of the January Senate runoff elections, Biden urged civil rights leaders to avoid bringing up the issue of police reform because Republicans had successfully labeled Democrats in swing districts as anti-police.

“That’s how they beat the living hell out of us across the country, saying that we’re talking about defunding the police,” he told the gathering. “We’re not. We’re talking about holding them accountable. We’re talking about giving them money to do the right things.”

With an eye on the 2022 midterms, Republicans this year have continued to use the defund the police movement as a cudgel against Democrats.

When the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed the House last month, Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said unfunded mandates in the measure would cost police departments hundreds of millions of dollars – “the equivalent of taking 3,000 cops off the streets.”

“Our men and women in uniform deserve better,” he tweeted. With both sides in perpetual campaign mode at the national level, there’s little chance to make headway on police reform in Congress, lament those who have tried and failed.

Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, the only black Republican serving in the upper chamber, last year worked to forge a middle ground but has grown increasingly frustrated by what he views as Democrats’ unwillingness to compromise and pass legislation that both sides can support.

Amid last year’s violent protests over Floyd’s death, along with several other black men and at least one woman who died at the hands of police, Scott spoke up about his own unsettling encounters with law enforcement, including one year in which he was stopped by police seven times.

“I, like many other Black Americans, have found myself choking on my own fears and disbelief when faced with the realities of an encounter with law enforcement,” he wrote in an op-ed in USA Today.

Scott then authored a bill that he says overlaps with the leading Democratic police reform legislation and includes action aimed at ending police use of chokeholds by withholding funds from localities that don’t ban the practice. Among numerous other provisions, Scott’s measure, like the Democrats’ version, would provide more funding for community-based policing programs and require data collection on policing practices. It would also create grant programs for police body-warn cameras, along with imposing penalties for failing to ensure the correct usage of them.

The bill, however, lacked the main element Democrats have been pushing: It did not include any changes to “qualified immunity” — the legal doctrine that protects police and other government workers from being held personally liable for misconduct except in very limited circumstances. The same Democrats who today are excoriating the Senate’s filibuster tradition filibustered Scott’s measure last summer when Republicans held the majority, preventing it from reaching the floor for a vote.

Scott says he’s open to modifying the immunity protections, but nearly all of his Republican colleagues view such efforts as poison pills – something too many of their supporters would never accept.

“Leadership starts at the top – full stop,” Scott told RealClearPolitics in a statement. “I am open to having conversations on civil qualified immunity as it relates to police departments, cities and municipalities being held accountable for the actions of those they employ.”

But, he added, he’s “disappointed” that the House has decided to vote on a partisan bill in “an attempt to fix a non-partisan issue.”

“I hope my friends on the other side of the aisle will come to the table to find common ground where we can make meaningful changes that will bring us closer to the goal of a more just country,” he concluded.

But without nuking the filibuster, the immunity issue remains a stumbling block for changes to federal law that would impact the entire country. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court provided a “qualified immunity exception” to protect government officials from being sued if they were acting in good faith and didn’t know that what they were doing was illegal.

Knowledgeable reformers also emphasize that the administration need not wait for changes on Capitol Hill. Marc Morial, for one, says he would like to see Biden’s law enforcement team, once confirmed and installed at the Justice Department, start ushering in changes to police policies across the country that don’t require congressional action.

Other advocates for imposing more accountability measures are looking to states to blaze the reform trail. Keith Neely, an attorney at Institute for Justice, a libertarian nonprofit, notes that Colorado and New Mexico have passed ground-breaking new laws aimed at limiting qualified immunity when police have engaged in proven misconduct.

Colorado’s law allows police who violate people’s civil rights to be held personally responsible in civil court if local authorities rule that the officer wasn’t acting under “reasonable belief that the action was lawful.” Officer fines would be capped at 5% of the damages, up to $25,000 of their own money, while cities and counties would be forced to pick up the tab for most cases of alleged police misconduct that doesn’t meet the “reasonable belief” threshold.

New Mexico passed a similar measure, though it requires cities, not individual officers, to pay fines and other court-ordered restitution. That bill is still awaiting the governor’s signature while similar measures limiting immunity have been introduced in states as diverse as New Hampshire and Texas.

Police unions, including the largest, the Fraternal Order of Police, have strongly opposed the idea of rolling back these protections. Doing so, the unions argue, would severely hurt cities’ ability to recruit and retain officers.

“People think that police officers have a free rein to do whatever they want and they are not held accountable,” but that’s not true, Rob Pride, a Loveland, Colo., police sergeant and the highest ranking black member of the union, said in an interview with the Marshall Project (an online journalism nonprofit focusing on criminal justice issues) that qualified immunity “does not prevent police departments from firing officers.”

But reformers are looking for more than cities finding the backbone to fire rogue officers after the fact — the Minneapolis Police Department fired Chauvin the day after Floyd’s death. They want to prevent such violent events from taking place. Holding localities responsible for writing bigger checks for legal payouts will likely make them vet their law enforcement employees more carefully and provide more training to prevent misconduct, Neely said.

That’s the mindset taking root in Colorado and New Mexico, where Democrats control the governor’s office and the legislature. Some advocates believe states are a better venue for these types of reforms because they can tailor them to local needs rather than be forced to accept one-size-fits-all marching orders from the federal government.

For instance, a compromise in Colorado’s reform law gives local city leaders – not an independent oversight agency – the role of deciding whether an officer acted in good faith and, therefore, doesn’t have to personally pay damages.

“Federalism allows for states to serve as the laboratories of democracy, and I think that’s true,” Neely said. “States have this unique ability to try new, innovative policies on the local level that folks aren’t ready for on a federal level or may not work properly at a national level.”

For instance, Neely said, changing state law could shift the legal venue for many of these police brutality cases. Americans are allowed to sue law enforcement or other government officials who they believe violated their constitutional rights, and most of these cases have been brought in federal court because state courts traditionally offered fewer civil rights protections. States that weakened qualified immunity protections for police could start seeing far more cases.

“It’s impressive what the states have already been able to accomplish,” Neely said. “And I have every reason for optimism that progress will continue to move forward at the state level, and that states will be the driving force for national change.”