(Steven Hayward)

The hottest thing among leftist political economists is “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT), which holds that a sovereign government can borrow and spend all the money it wants because it can’t actually default on its own currency. This warmed-over Keynesianism wouldn’t get anywhere except in a time of unusually low interest rates and very low inflation.

One of the leading advocates of MMT is Stephanie Kelton of Stony Brook University, the author of The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. You’d be right to suspect anything called “the people’s economy,” just as every “people’s republic” of the last century has been a leftist dictatorship. Funny how that always seems to happen when someone uses “people’s” in this fashion. Kelton does for economics what Howard Zinn does for American history, and this parallel may not be coincidence.

MMT, like Keynesianism back in the New Deal era, is a convenient theory for politicians who want to spend lots of money. Kelton was an adviser to, I believe, both Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, but it is not clear how much pull she has with Biden’s inner circle. One question I’ve been wanting to ask an MMT advocate since the beginning is: if we can borrow all the money we want without limit and without consequence, why raise taxes on anyone, as Democrats always want to do? For that matter, why tax anyone at all, if you can borrow (print) all the money you want?

The latest issue of the Journal of Economic Literature, a mainstream academic journal, has a scathing review of Kelton’s book by Alberto Bisin of New York University, whom I’ve never heard of before, but I note he earned his Ph.D from the University of Chicago, which is a promising sign. He thinks Kelton’s book is mostly rhetoric and very little rigor. Some samples:

The book should be seen as a rhetorical exercise. Indeed, it is the core of MMT that appears as merely a rhetorical exercise. As such it is interesting, but not a theory in any meaningful sense I can make of the word. The T in MMT is more like a collection of interrelated statements floating in fluid arguments. Never is its logical structure expressed in a direct, clear way, from head to toe. . .

There are even contradictory statements about MMT in the book, but they are kept vague and far enough apart from each other that they are not easy to spot. For instance, on the central issue of government budget constraint, a statement to the effect that monetization is not without limits is repeated a few times in the book, for example, “MMT is not a free lunch” (p. 37), and “MMT is not about removing all limits” (p. 40). But these statements leave no dent on the core message of MMT—that a sovereign government has no need to finance its spending. It is said that inflation is what limits monetization. But the role of inflation is left dangling, seemingly unrelated to fiscal policy or to agents’ expectations. . .

MMT, as exposed in the book, appears to be a very poor attempt at supporting this [big spending] political agenda, with no coherent theoretical support.

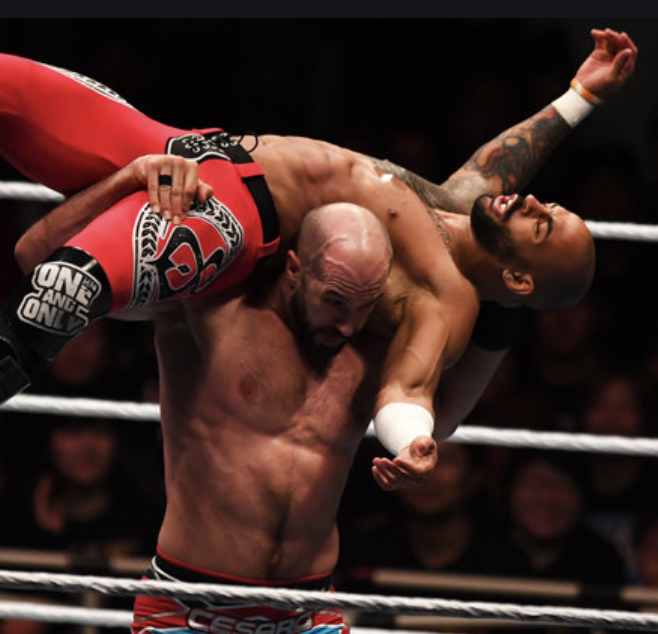

And this is the point where Donald Trump walks into the ring in the WWF arena and throws Vince McMahon to the floor.