One of the interesting things about Donald Trump’s upset win in 2016 was that, in retrospect, all the signs were there: It was obvious in the immediate aftermath that key swing states in the Midwest were under-polled; it was obvious that polls were undercounting whites without college degrees; and it was obvious that Trump was closing in on Hillary Clinton at the end, especially in the key states of Michigan and Pennsylvania. Still, it was difficult to put all that together into a coherent case for a Trump upset, especially since the arguments for Hillary Clinton winning were more prevalent and more straightforward. One thing that was not obvious was the magnitude of the looming split between the popular vote and electoral votes.

A similar situation exists today. It is much more straightforward to make the case for a Joe Biden win. He’s up seven percentage points in the RealClearPolitics Average of national polls, and leads in the key swing states. This lead has been durable and stable over the course of the race. The president has presided over an economic collapse and a pandemic that will have killed more than 200,000 Americans by the end of this month.

But what if Trump does pull out the win again? What will have happened? Or to put it differently, what’s the best case to be made now for how Trump is reelected? Setting aside the possibility for another substantial polling error in key swing states, which I discussed last week, the answer has three parts.

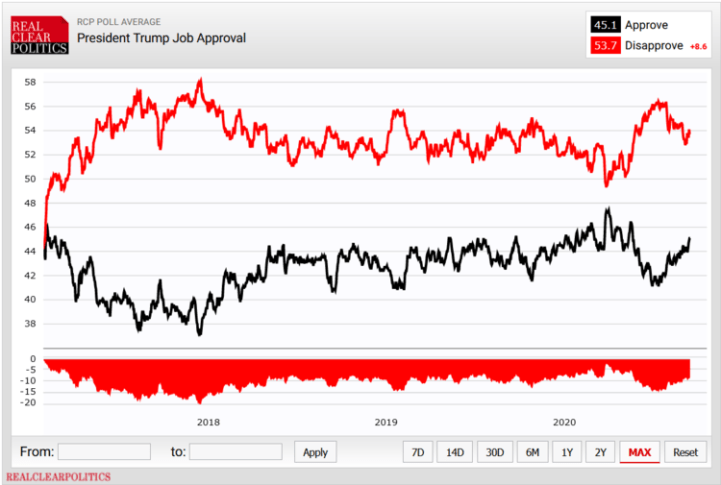

(1) Trump’s job approval solidifies. Earlier this summer, I posted a Twitter poll asking respondents what level they believed Trump’s job approval would have to reach in order for him to be favored to win. The response mode was around 46%.

This answer makes sense. Exit polls show that presidents typically receive a vote share that is roughly in line with their job approval. This isn’t particularly surprising: Elections tend to be referenda on the party in power. If you like the job the president is doing, you vote for him. If you do not, you vote against him. So when Barack Obama won reelection in 2012, his job approval in the RCP Average was 50%; he won with 51% of the vote. When George W. Bush won reelection in 2004, his job approval was just shy of 50%; he won with just under 51% of the vote. Presidents tend to get the votes of those who think they are doing a good job, and maybe a hair more.

The reason 46% makes sense for Trump is because we are pretty sure that he can win with 46% or 47% of the vote. After all, he did so in 2016 (Gary Johnson may have siphoned off some of his support, but Jill Stein likely did the same Hillary Clinton), and it appears from polling that the Electoral College/popular vote split is about the same today as it was in 2016, if not a bit larger. So what is Trump’s job approval doing today?

It is rising, and at a fairly steady clip. He isn’t at the 46% threshold yet, and it’s likely he’ll level off in the next few weeks, but that isn’t a given.

This is, frankly, a much better position for Trump to be in than the two most recent presidents who lost their reelection bids. President George H.W. Bush’s job approval was consistently in the mid-to-high 30s post-Labor Day, while Jimmy Carter’s job approval was in the low 30s. Trump’s job approval isn’t good, but it is closer to that of recent presidents who have won than to recent presidents who have lost.

Finally, in this vein, one of the more perplexing features of 2020 is that Trump’s job approval has outpaced his vote share in head-to-head polls. Who are these people who approve of the job he is doing but don’t plan on voting for him? My guess is they are eventual Trump voters, who either won’t admit to themselves or to the pollster that they are going to vote for him. Perhaps Trump will lose a substantial number of people who approve of the job he is doing, but I’m not sure I’d bet on it.

(2) The economy continues to improve. Elections are referenda on the party in power, but the most salient aspect of an incumbent’s performance when choosing whether to vote “yea” or “nay” is the state of the economy, particularly the state of the economy in the second quarter of the election year.

This election is tricky in that respect. Growth in the second quarter, as the pandemic started taking its toll, was abysmal, in such a way that we have no historical comparison for it, at least for time periods where we have good data. Yet growth in the third quarter appears to be explosive, potentially wiping away most of the contraction that occurred in the second quarter. There is simply no precedent for this either.

Perhaps because of the unusually strong growth in the third quarter, or because people appreciate the unique reason for the economic contraction in the second quarter (i.e. we shut everything down to try and slow a virus), the president’s approval rating on the economy has rebounded, and he is once again viewed positively on the economy. Perhaps more importantly, as you can see on page 16 of this release, he is now trusted more than Joe Biden on the economy by a 52%-44% margin, a reversal from the early summer.

We should be careful not to be reductionist. Voters don’t only vote on the economy, and Biden leads Trump on most other issues. But if Trump were to win, changing perceptions of his performance on the economy would likely be a key reason why.

(3) Biden’s problems with the base are real. Every cycle we hear stories about the other party having problems with its base. Some of them do not pan out – despite the hopes of progressives, Obama did not perform well with evangelicals in 2008 or 2012 – but sometimes they do.

So the spate of recent stories suggesting that Biden is having difficulty generating Hispanic and, to a lesser extent, Black support is at least worth taking note of. I don’t read too much into it right now — these stories are hit-and-miss in their accuracy — but if Biden loses this will likely be a large part of it.

Again, none of this is to be taken as a prediction as such – this is a race that could go either way and where I still view Biden as the favorite. With that said, the storyline sketched out above is perfectly realistic. If Biden does lose, we will likely look at these factors and conclude that we should have seen it coming.