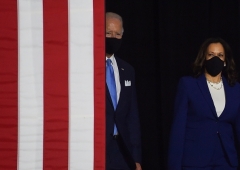

Joe Biden and his vice presidential running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, arrive in Wilmington, Delaware, on Wednesday for their first joint campaign appearance. (Photo by Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images)

(CNSNews.com) – Sen. Kamala Harris, Joe Biden’s vice presidential pick, has little foreign policy experience, although positions she has taken align largely with those of the presumptive Democratic nominee, including on rejoining the Iran nuclear deal and correcting what critics view as President Trump’s inappropriate treatment of NATO.

One key foreign policy issue on which she has differed with Biden is the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the successor to the 25-year-old NAFTA. While Biden supported the renegotiated trade deal, Harris was one of ten senators to vote against it last January, calling its environmental provisions “insufficient.”

Biden’s supporters see him as a foreign policy heavyweight, given his two terms as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and involvement in foreign affairs while vice president.

By contrast Harris, a first term senator, is a former California attorney general and San Francisco district attorney.

Still, Biden said during a fundraiser on Wednesday that Harris was “even more up to date than I am,” because of briefings she receives as a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee.

“Until three weeks ago I didn’t get briefed every day,” he said, according to a pool report, before adding, “I get briefed every day again because I’m the de facto nominee.”

While running for the presidential nomination Harris criticized Trump for withdrawing from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. Like most Democrats in Congress, she opposed the decision at the time to exit what Trump called “a horrible, one-sided deal” that should never have been made.

The Obama-Biden administration touted the JCPOA as one of its most significant foreign policy accomplishments, although Biden’s position has become more nuanced since then.

Campaign foreign policy advisor Tony Blinken said in June Biden would return to compliance if Tehran did, but would then look to partners and allies to support efforts to “negotiate a longer and stronger deal.”

Similarly Harris, while running for the presidential nomination, said that as president she would rejoin the JCPOA “so long as Iran also returned to verifiable compliance.”

“At the same time, I would seek negotiations with Iran to extend and supplement some of the nuclear deal’s existing provisions, and work with our partners to counter Iran’s destabilizing behavior in the region, including with regard to its ballistic missile program,” she said in response to a Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) candidates’ questionnaire.

(Before withdrawing from the JCPOA Trump, too sought European allies’ support to “fix” the agreement, but without success. His objections included limitations on inspections at suspect military sites, “sunset clauses,” and the deal’s failure to require Iran to stop its ballistic missile program.)

Harris’ approach towards NATO is also aligned with Biden’s.

In a debate in Miami in June last year, when candidates were asked to name the first relationship they would “reset” once in the Oval Office, Harris – like Biden – said the one with NATO. (Others on the stage named China, Iran, European allies, Latin American countries, and the United Nations.)

Critics accuse Trump of jeopardizing U.S. ties with NATO. The president has irritated some, none more so than Germany, with repeated criticisms of deficient military spending, but has also drawn praise from NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg for successfully prodding allies to meet their defense spending commitments.

Biden said at Wednesday’s fundraiser that if he’s elected he’ll be on the phone directly to tell NATO allies “we’re back.”

“We’re not going to abandon our friends. We’re not going to walk away. We’re not going to treat NATO like a protection racket,” he said.

China, Saudis, Israel, North Korea

On other foreign policy issues:

–Harris says the U.S. should cooperate with China on issues like climate change and North Korea, but challenge Beijing on rights abuses and IP theft.

–Harris opposes U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia, given the humanitarian crisis exacerbated by the war in Yemen. That’s a position shared by all Senate Democrats, and a handful of Republicans. Biden says that as president he would not sell arms to Riyadh, citing the murder of Jamal Khashoggi. (The Obama-Biden administration sold the kingdom around $112 billion in weapons over its two terms.)

–Harris has voiced support for Israel and the so-called “two-state solution” to the conflict. She addressed the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) policy conference in 2017 and in 2018, but like most Democratic presidential hopefuls – Biden was an exception – she stayed away from its conference this year. (She did meet on the sidelines with California AIPAC members at her office.)

–Harris voted against bipartisan legislation in 2019 enabling state and local governments to divest from any company or fund that boycotts, divests from, or sanctions Israel. (It passed 77-23.)

–Harris said last November Trump “got punked” in his diplomacy with Kim Jong Un, and that as president she would not offer any concessions to Pyongyang. But in the earlier CFR questionnaire she said she would consider targeted sanctions relief in return for “serious, verifiable steps to roll back” the regime’s nuclear program. That’s essentially the approach attempted by the Obama-Biden, George W. Bush, and Clinton administrations between 1994 and 2012, all without success.

–Harris co-sponsored a Senate resolution last summer declaring “a climate emergency which demands a massive-scale mobilization to halt, reverse, and address its consequences and causes.”

–Harris supports recognizing mass killings of Armenians in Ottoman Turkey a century ago as a genocide. She was among 20 co-sponsors of a bipartisan resolution on the issue passed by the Senate last December.

.jpg?fit=60,43&ssl=1)